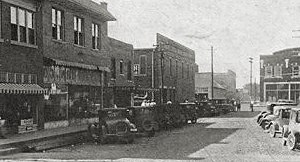

More than anything else, Wynne, Arkansas had the railroads to thank for its relative prosperity. With a population of three thousand, it was the largest city in the county as well as the county seat. Two other cities had vied for Wynne’s prominence, but had failed. Wittsburg, seven miles to the southeast and Vanndale, five miles to the north, had preceded Wynne as the centers of county government. But while both towns still existed, neither one had had what was necessary to attract eastern money men. Wynne did.

Wynne had the good fortune to be selected in the late 1800’s as a major crossroad for the Missouri Pacific and the L & J lines. From Wynne, a company could ship to literally anywhere in the country. So from almost the first day that tracks were being laid, rice dryers, cotton gins and implement companies, just to name a few, began construction in or movement to Wynne. And naturally, the people followed

So now, nearly forty years after those tracks were laid, Wynne was a small city of two pool halls, one bar, two liquor stores and seven churches of various denominations. The primary sources of commerce in the area were still farming and ranching. But on weekends, the streets bustled with retail activity from the goodly number of stores that were now there. And even though it would be nearly twenty years before Wynne would have its first factory and begin to delve into real commerce, the town still attracted country boys like bees to pollen. Marshall and George were no different.

As farmer’s kids, they both had learned to drive at an early age, but that Friday night they walked because, as Carl Bentwood would have put it, it was an “unnecessary trip”.

If they had been going to the store for flour, cornmeal, sugar, or some other staple, they could have ridden a horse or mule. For a load of cotton seed, egg pellets, or corn chops, using the truck would have been justified. But, for a person going to town just to “play,” the only sort of transportation allowed was walking……so, they walked.

By the time they had traversed the two and a half miles to the edge of town, where the dirt and gravel changed to concrete, it was 9:00. After walking two hundred yards up the street, a car pulled up from behind and drove beside them as they walked. It was Thomas and George’s brother, Simpson in Simpson’s 1932 Ford roadster. It was normally dusty as most cars from in the country were, but apparently Simpson had just finished washing and polishing it because its ebony surface gleamed in the moonlight.

“Ain’t it a little late for you boys to be out?” Thomas grinned. “They have a curfew for babies, ya know.”

“Mind ya own business, Tom.” Marshall said, not looking at his brother.

“Took ya’ll a while ta get here, didn’t it?” Thomas grinned. “Sim had time to come get me and we done drove round town and ya’ll just now ta here. Must be terrible havin’ ta walk everywhere.”

“Hey, boy,” Simpson yelled at George whom he never called by name. “Does Daddy know where you are?”

“What Marsh said goes for you, too, Sim,” George said. “Mind ya own business.”

“Marsh,” Thomas pointed at his brother. “Ya better remember what Daddy told you at supper. He catches ya fightin’ again and he will skin ya. And didn’t the cops tell ya they’d lock ya up the next time they had ta pull you offa somebody?”

Marshall’s eyes were barely more than slits as he stopped and stared at his brother.

“Leave us alone, Tom, or they’ll be pullin’ me offa you.” It was a menacing tone that Thomas knew well and older brother or not, he knew when to back off.

“Well, me and Sim gotta be goin’ anyway,” Thomas said. “We don’t have time ta mess around with you girls.”

Without waiting for a response, the two men sped off leaving their younger brothers once again in the dark.

“Sometimes I hate him.” Marshall said as they began walking again.

“Aw, don’t worry about it, Marsh.” George said. “They’re just jealous.”

“Jealous! Jealous of what?”

“Of us,” George feigned mock surprise that Marshall did not know the reason. “They just wished that they’s as young and good lookin’ as we are.”

Marshall snickered then said, “Well, anyway, what’cha wanna do?”

“Let’s go ta tha pool hall first.” George said.

“What’cha wanna go in there for, them old guys cleaned ya out last time?” Marshall answered the suggestion.

“I feel lucky tonight.” George’s eyes gleamed.

“That don’t mean nothin’. Ya felt lucky that night and ya didn’t win a game.” Marshall said trying to be realistic, but George would have none of it.

“It’ll be different tonight, I promise ya.”

“We’ll see.” Marshall said, resigned to tag along, at least for the time being.

George fancied himself an excellent pool player, when, in reality, he was average at best. Even Marshall could beat him occasionally and he didn’t even care about the game. The regulars at Sully’s Pool Hall built him up, of course. They knew when they had an easy mark and were more than willing to oblige George in his apparent quest for poverty.

The two boys pushed through the front door of the hall and were immediately met with the odors of beer and cigarettes and sweat and aged pine. The freestanding building was long and narrow, twenty-feet wide by eighty-feet long, with a plank floor and 12-foot-high tin covered ceilings.

Six long bladed fans hung from the ceiling, spaced evenly down the center of the room. Peeling wallpaper partially covered the walls and where it did not, plaster lathing slats were visible. Pool cue racks, some full of cues and extra balls and some not, hung on much of the wall space, prepared to go to battle at a moment’s notice. The building had been recently wired for electricity and the resulting lights hung above the pool racks at eight-foot intervals on both walls. Plus, naked bulbs hung on five-foot cords down the length of the building at the same intervals as the wall lights.

A black pot belly stove stood in the center of the building three quarters of the way to the back. It was audibly roaring as it fought against the early March cold. Behind the stove were three wooden tables with chairs around each. At these tables, poker was occasionally played, but more often, the game was dominoes. That night, all three tables were filled with men of various ages, each with a line of black or white dominoes in front of them. No one looked up when the boys entered the building.

In front of the stove were four average pool tables, two abreast, eight feet apart. Over each table counting beads were strung on wires that stretched from wall to wall. In front of these four was the first thing everyone saw as he entered the establishment, the “prime” table.

It stood perpendicular to the other tables, as if to show that it was the best, but any true pool player would have known that immediately. It was heavy, made of solid oak, polished to a high sheen, with green felt covering its two-inch slate table bed. The position marks on the table rim were made of inlaid ivory and it had six massive clawfoot legs that looked capable of pouncing at any time. Well oiled, leather pockets completed the look. It was, without a doubt, as good a pool table as there was anywhere in the state…….including Little Rock

“C’mon in boys,” ‘Sully’ Sullivan said from behind the bar that ran along the wall to the right. It was from that bar that he sold beer legally and a few other things under the table.

The only thing Sully ever sold to minors, though, was a game of pool, a root beer, or a piece of hard candy. And since everyone in town knew it, there was never any fuss about the occasional teen who came in. That opinion, however, was not shared by the church going crowd who looked upon the establishment as a “den of iniquity” and home for the devil.

“Gonna try ya hand at another game, Borden,” Sully said. He used George’s last name as he did all the area boys who came into his business. Most of them liked it…..made them feel older.

“Yes, sir, Mr. Sully,” George grinned and placed a dime on the counter. “Rack ‘er up.”

“Big spender,” Marshall mumbled. His friend could have played on one of the other tables for a nickel. But George being George, he wanted to show whoever might be looking that he meant business, so he started out on the main table. To him, it was worth the extra nickel.

Sully picked the dime up and nodded to a shadowy area of the room where chairs were lined against the wall. Almost immediately, Ned, the black rack man, janitor, etc., appeared out of the darkness.

The hunched old man hobbled around the table digging balls from the pockets and rolling them toward the racking dot. Once finished, he threw them into a triangle he had pulled from its place under the table, tightened them with arthritic thumbs and fingers then carefully lifted the triangle off.

Marshall watched as George confidently set the cue ball in position and after a careful aim, sent it hurtling into the rack. It smashed into the group with a satisfying “crack”, sending colored balls in all directions.

George looked at Marshall as if to say, “I told you so,” Then after taking careful aim, proceeded to miss his first shot. As George cursed the cue stick, Marshall said, “I’m goin’ outside for a minute.”

“Yea, fine,” George said, lining up his next shot.

Marshall meant, of course, that he was going to the outhouse behind the pool hall. As he walked to the back door, he passed the men at the card tables and nodded at them collectively. Some responded with “Marsh,” while others said “Bentwood,” but all at the very least nodded.

After the warmth of the building, the cold of the March weather bit at him as he walked through the back door onto the low outer porch. Marshall stepped onto the wooden walk that led straight to the small “one-seater” some fifty feet behind the main building.

In the fall and winter, the short distance to the outhouse wasn’t a bothersome thing, but in the heat of a Delta summer, everyone’s nose quickly told them that the building was too close to the pool hall. Sully had gotten several complaints about it, but he always said if he could stay in the hall all day and stand it, so could others for a couple of hours or so.

Marshall was about halfway to the “outie” when he gazed past the building to the landscape beyond and stopped. Under the low, full moon he could make out the silhouette of the Ridge.

The Ridge, as everyone called it, was an anomaly. Nothing resembled it for over 75 miles in any direction. Some said that it had been formed centuries ago by a great earthquake on the New Madrid Fault which ran from southern Missouri down into Arkansas. Others said the Mississippi had something to do with it (probably because “Old Man River” was such a presence in the area).

The theory Marshall subscribed to, because he had heard it in geography class, was that it was formed in the Ice Age when a turning-plow shaped glacier started inching its way down from the north. Somewhere about eighty miles north of Wynne, the glacier began turning the earth over onto itself, and inch-by-inch continued to move southward

It kept on plowing until it got almost to where Helena would later be founded, sixty miles south of Wynne, then for some reason no one would ever know, it just stopped. So now what had resulted thousands of years later was a badly healed scar called Crowley’s (pronounced like the bird and named for some founding father in the past) Ridge in the Eastern Arkansas area of the Delta.

The Ridge was indeed a thing of beauty. Over a hundred miles long, 300 feet high at its highest, between one-quarter and five miles wide it ran as straight as any such thing in nature ever did. It was covered with pine saplings and rich meadows, wading ponds and bass lakes, Angus and Herefords and Walkers, shotgun shacks and Anti-Bellum mansions, stills and God only knew what else. It wasn’t maudlin to say that it truly was the heart of the area.

The Ridge had always been a glorious presence to Marshall. It broke up the monotony of the cotton, bean, rice, sorghum, and corn fields that he had grown so tired of. He wanted to see and do things in this life, and he would relish any sort of change from the mundane life of a farmer. But the Ridge was the one thing in that life that he hoped would never change.

After a few minutes of staring at the Ridge, Marshall shivered suddenly feeling the March cold. Then he realized that he hadn’t even finished the business that he had come outside for. So, he quickly took care of the matter then hurried back toward the pool hall.

Marshall had gotten almost to the back porch when he heard shouting coming from inside. He ran the rest of the way to the building and threw the door open just in time to see George by the main table burying his right fist into the stomach of a man Marshall knew as Bill Prichard.

A split second later a second man that Marshall didn’t recognize broke a pool cue across the back of George’s neck. The broken piece flew across the room and slammed into a pool cue rack on the opposite wall causing cues and balls to crash to the floor.

“George,” Marshall yelled and started running toward his friend as he saw him fall limply across the table, face down. Out of the corner of his eye he could see Sully reaching under the bar for the sawed-off 20-guage Marshall had seen him bring out once. It was shorter than the legal limit, but the barkeep told him once that the cops had always let him slide. The way these two men looked, however, Marshall knew something had to be done quicker than Sully was moving, so he grabbed the coal poker from beside the stove as he rushed forward toward the two twenty-something men.

Some thirty feet from the front of the hall, he sent the poker spinning toward Prichard who had just picked up a stray cue and was positioning himself to bring it down on the back of George’s head. Before he could deliver what surely would have been a killing blow, however, the poker slammed flatly across his open chest. He grunted from both surprise and the force of the blow then crashed backward onto the plank floor; his breath instantly shoved from his lungs. He laid gasping and never saw Marshall until the teen’s work boot landed solidly across his left ear. Then he passed out.

Marshall turned to the other man quickly and saw that he was reaching into his coat pocket. But, before he could get his filled hand free, the teen jumped across Prichard’s limp form and hammered his fist down onto the man’s right cheekbone twice in quick succession. Then in almost the same motion he brought the heal of his left hand up against the man’s chin snapping his head back. He instantly went limp and crumpled to the floor at Marshall’s feet.

Marshall stood for a moment panting, fists clinched, trembling, eyes and nostrils flared. He looked around and saw that Sully as well as the men at the back of the hall were standing or sitting in frozen awe at what they had witnessed. As Marshall slowly unclenched his fists, he heard a moan. It was George.

“George,” He said then turned and put his hand on his friend’s back. “George, ya ok?”

He pushed his friend’s shirt collar down to see if there was any blood. There wasn’t although a huge, blue-black knot had come up just at his hair line.

“What’d he hit me with,” George said as he gingerly rubbed his neck while slowly raising himself off the table. He looked to the side, behind Marshall and saw the men on the floor. “Durn, Marsh, did you do that?”

“The guy with Prichard caught ya with a cue,” Marshall ignored his friend’s second question and answered the first. “Who is that other guy?”

George glanced at Marshall, “If ya don’t know now, ya better off not knowin’ ‘im.”

Prichard began moaning, but the second man had not moved yet.

Sully who had been frozen behind the bar during the confrontation, finally spoke, “Borden, you all right?”

“Yes, sir,” George continued to rub his neck. “I think so.”

“Good,” Sully said, relieved. “Ya know I gotta call tha cops boys.”

“Naw, Mr Sully!” George whined. “Ya don’t have ta do that.”

Marshall said nothing.

“Got to, boys,” Sully answered. “I don’t know what’s goin on between you and these guys, here, but I do know that they’re adults and they jumped a minor. So, unless one of ya’ll’s done somethin bad illegal, I don’t think ya have ta worry about nothin’.”

Sully didn’t say so, but everyone knew that he had had a number of run-ins with Prichard, so it gave him a good deal of pleasure to see him get a “comeuppance.”

“Did he kill ‘em,” Eighty-year-old Eldon Chapman called from the back of the room, but not bothering to look up from his freshly dealt domino hand.

Sully walked over to the two men and looked to see if they were breathing……..they were.

“Na, they’ll survive,” He called to the domino bunch.

“Well, let Marsh go,” George pleaded. “He was just helpin me.”

“Sorry, boys,” He shook his head as he walked back behind the bar. “No need for Bentwood to run, anyway. Everybody in town knows who he is and the cops for sure know where he lives. So just make ya self ta home and we’ll get it all straightened out.”

Sully picked up the phone receiver on the end of the bar and spoke into it almost immediately. “June, gimme the Chief’s house, he’s probably left the station by now.”